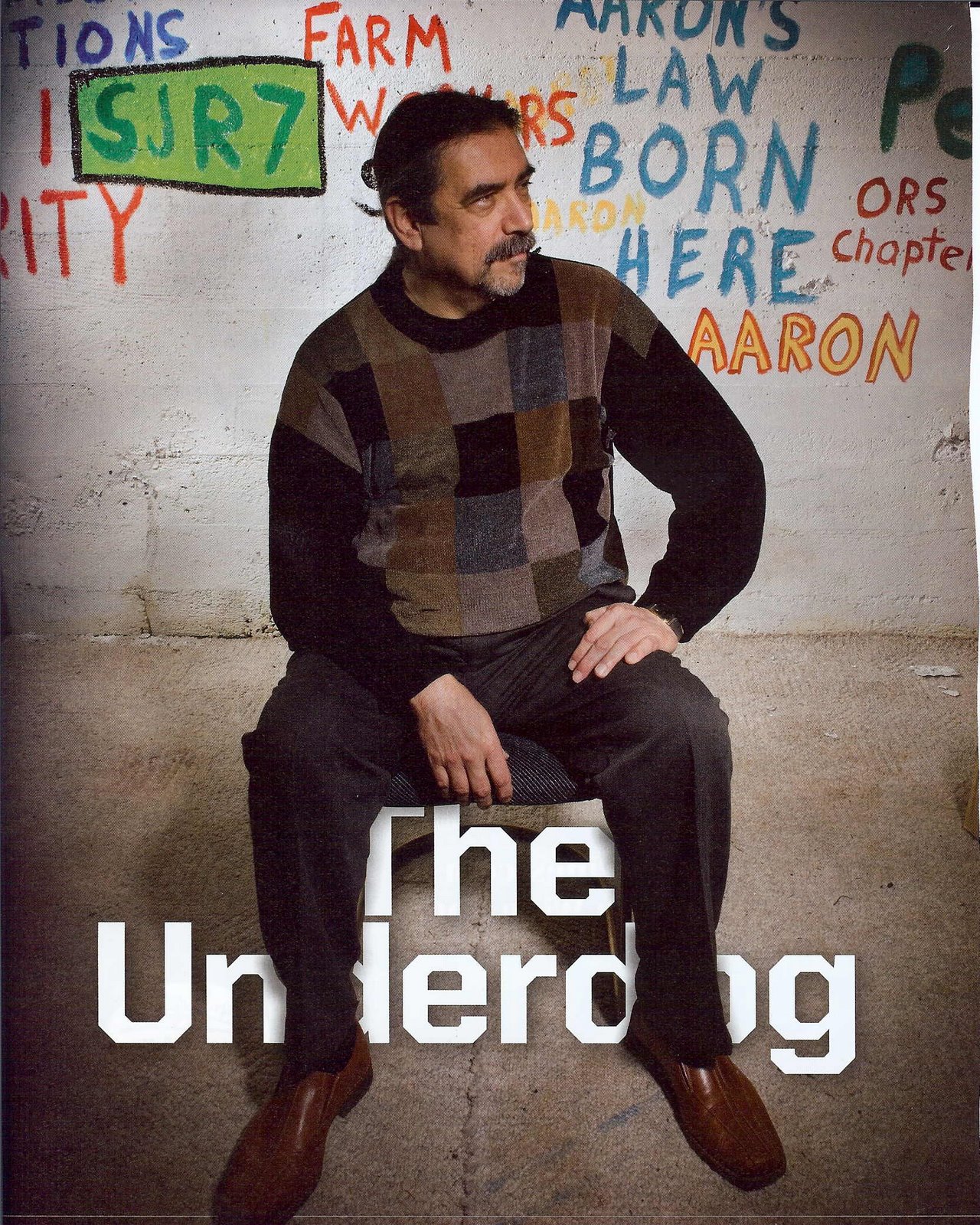

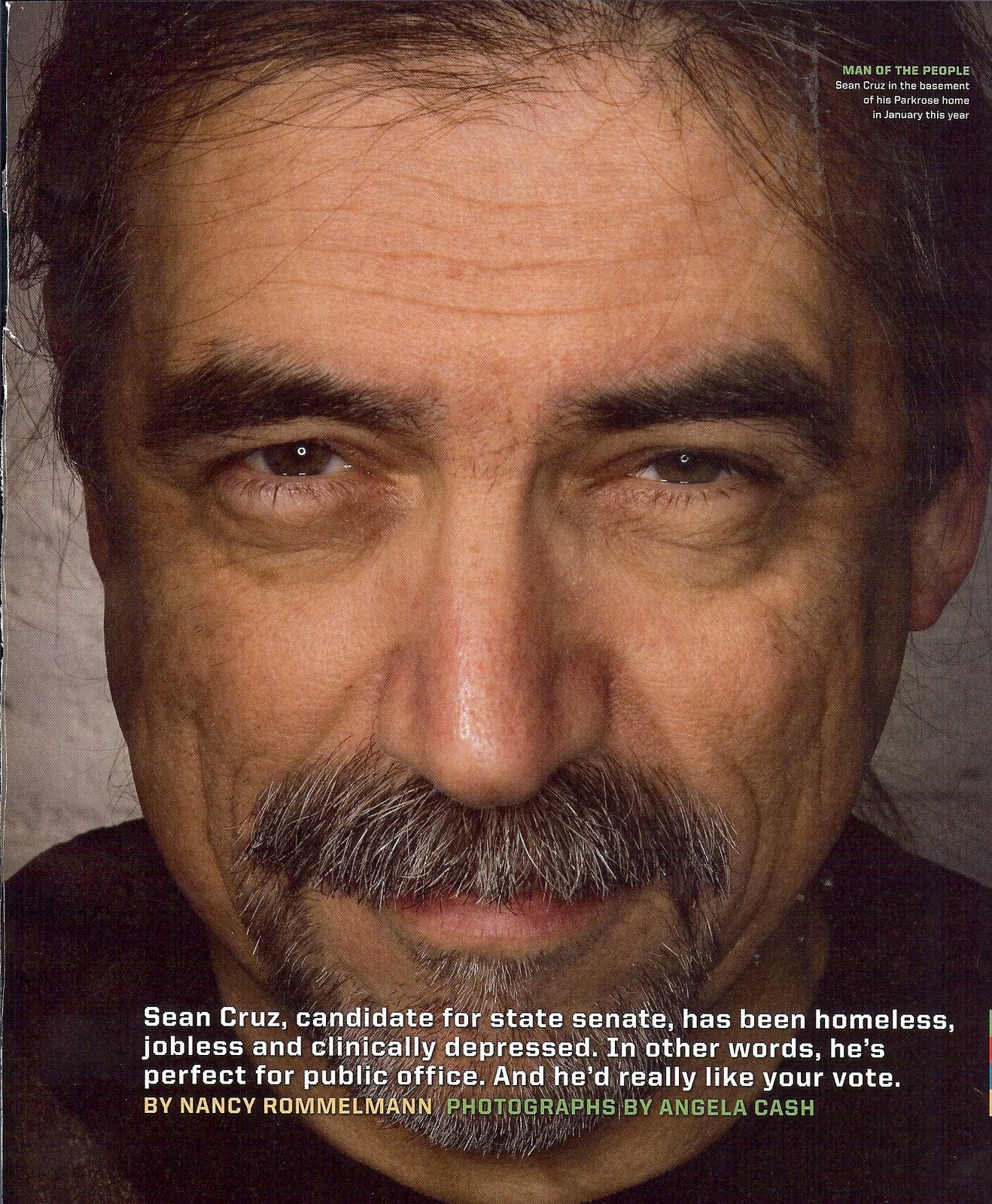

by Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon--

It was fifteen years ago, on February 12, 1996, that my four children vanished from Oregon, taken into concealment in a series of remote Mormon enclaves in theocratic Utah. They certainly take care of their own, those Mormon ideologues do. Mormon officials in three states were involved in planning, carrying out and maintaining the kidnapping.

No independent thought is permitted among Mormon children. My son Aaron had a strong independent streak in him, however, and they punished him for that, eventually wearing him down, taking away his hopes and dreams in that ratty Mormon town where he died in 2005, in Payson, Utah.

In 2005, I watched Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski sign Senate Bill 1041 into law, named "Aaron's Law" after my son. With Aaron's Law, Oregon is the only state in the nation where child abduction creates a civil cause of action.

If Aaron's Law had been on the books in 1995, no abduction would have taken place, my family would have remained whole, healthy and happy like we were, and my son would still be alive today.

Sunday, February 13, 2011

Wednesday, February 02, 2011

A message in a bottle

Today is my baby girl’s birthday, and life beckons anew

A message in a bottle

Allie, my baby girl, was just a few days past her 8th birthday when the Mormons made her disappear, fifteen long years ago. She has lived in a succession of Mormon enclaves ever since, surrounded by Mormon ideologues, some with criminal culpability in the abduction of my children. They have focused their energies on severing every connection she might have to her birth family, on keeping her within the confines of the Mormon church, in part because that’s the way they do things in the Mormon world, but also to hide their crimes, especially from her.

The statutes of limitations have run on their crimes long ago, but not their consequences.

Any abduction of a child has lifelong consequences; no one is ever the same again. Some victims die as a result, like my son Aaron, who never had a chance at happiness again, after vanishing with his siblings into concealment in a succession of remote locations in Utah on February 12, 1996.

We live in a world where some parents can suffer the loss of a child and barely notice, a world where far too many children have been left behind by the very two people who gave them life, where far too many young people know this is what they can expect from their mom and/or their dad.

It is a world where some parents will sacrifice their children for a fix, for a snort, for two dollars, to chase after a man or a woman, or to satisfy some religious craving or mandate, or for reasons that defy understanding on any level at all.

Some religious organizations—like the Mormons—are very effective at carving families into pieces, dividing them into Mormon and non-Mormon factions, and the church has institutionalized a culture of separation, even to the point of forbidding a non-Mormon parent from attending his or her own child’s wedding, if the family is unfortunate enough to have that circumstance arise.

I had the terrible bad luck to have a wife that well into our marriage woke up one day and decided she was going to commit her life to Mormonism, though she didn’t say that at the time, and there was no way to see this coming at all. Not a hint before the fact.

But I digress….

It took me fifteen years, from the day of my children’s disappearance, to get beyond mere survival, to arrive at a point where I can celebrate life once again.

That is what I am going to do today, I am going to celebrate life. I am going to live and be happy to be alive today, February 2, 2011.

And every day thereafter….

So I am putting this message into a bottle and sending it out on its way, and maybe someday it will arrive where you can find it, baby girl, and know that your daddy never stopped loving you…never ever stopped loving you…never stopped loving you…never…ever…to infinity…love you forever, Dad….

Here she is early in life. Photographs of her or my other children after February 12, 1996 are very rare.

To you, baby girl, on your birthday.

Love, Dad

A message in a bottle

Allie, my baby girl, was just a few days past her 8th birthday when the Mormons made her disappear, fifteen long years ago. She has lived in a succession of Mormon enclaves ever since, surrounded by Mormon ideologues, some with criminal culpability in the abduction of my children. They have focused their energies on severing every connection she might have to her birth family, on keeping her within the confines of the Mormon church, in part because that’s the way they do things in the Mormon world, but also to hide their crimes, especially from her.

The statutes of limitations have run on their crimes long ago, but not their consequences.

Any abduction of a child has lifelong consequences; no one is ever the same again. Some victims die as a result, like my son Aaron, who never had a chance at happiness again, after vanishing with his siblings into concealment in a succession of remote locations in Utah on February 12, 1996.

We live in a world where some parents can suffer the loss of a child and barely notice, a world where far too many children have been left behind by the very two people who gave them life, where far too many young people know this is what they can expect from their mom and/or their dad.

It is a world where some parents will sacrifice their children for a fix, for a snort, for two dollars, to chase after a man or a woman, or to satisfy some religious craving or mandate, or for reasons that defy understanding on any level at all.

Some religious organizations—like the Mormons—are very effective at carving families into pieces, dividing them into Mormon and non-Mormon factions, and the church has institutionalized a culture of separation, even to the point of forbidding a non-Mormon parent from attending his or her own child’s wedding, if the family is unfortunate enough to have that circumstance arise.

I had the terrible bad luck to have a wife that well into our marriage woke up one day and decided she was going to commit her life to Mormonism, though she didn’t say that at the time, and there was no way to see this coming at all. Not a hint before the fact.

But I digress….

It took me fifteen years, from the day of my children’s disappearance, to get beyond mere survival, to arrive at a point where I can celebrate life once again.

That is what I am going to do today, I am going to celebrate life. I am going to live and be happy to be alive today, February 2, 2011.

And every day thereafter….

So I am putting this message into a bottle and sending it out on its way, and maybe someday it will arrive where you can find it, baby girl, and know that your daddy never stopped loving you…never ever stopped loving you…never stopped loving you…never…ever…to infinity…love you forever, Dad….

Here she is early in life. Photographs of her or my other children after February 12, 1996 are very rare.

To you, baby girl, on your birthday.

Love, Dad

Tuesday, February 01, 2011

I can eat fire --an essay

I can eat fire

by Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon --Professor Tom Holm’s essay, “Patriots and Pawns: State Use of American Indians in the Military and the Process of Nativization in the United States”, goes far to explain why American Indians have enlisted and served in numbers that far exceed their percentage of the US population, despite the racist and hostile experiences that characterize the history of Native American peoples and the US military.

Native Americans volunteer for military service for the same array of reasons that non-Natives enlist, such as: family tradition, financial reasons, a desire to get away from home, to learn new skills, as a test of courage or to join battle with a specific enemy; i.e. Osama Bin Laden or Adolf Hitler. Professor Holm identifies several other factors specific to Native Americans to explain the phenomenon.

He also writes about the attitudes that shape military perceptions of Native Americans and that influence the roles that Indians are often called to serve in military operations, in how they are used.

Some Indian nations and Native American individuals have seen military service as a treaty obligation, a matter of honor; even though the US has rarely honored its own treaty commitments, their sense of honor requires their service.

Institutional factors, such as active recruitment efforts by the BIA and in Indian boarding schools, and discriminatory practices by local draft boards contribute to the enlistment numbers.

Holm briefly examines the relationships of ethnicity, political elites and the military. Throughout history, ethnicity has always been a vital part of the equation:

“In general, militaries not only protect the nation from foreign invasion, but promote the causes of and provide security for the hierarchical apparatuses of the state. In plural societies or imperial systems, state elites, both in uniform and out, have to judge which national or ethnic groups can serve in the military without turning the guns around and posing a threat to the state.”

Throughout history, ruling elites and nations have adopted many different strategies to incorporate vanquished peoples into their militaries, shaped by the dominant culture’s view of the subjugated ethnic groups, and by their perception of the potential threat. Holm suggests that an important reason that the US military has not felt threatened by its Native American service members is because the population is so few in number, such a small percentage of the total force.

Holm observes that incorporating Native Americans into the military is a method of assimilating them into the melting pot, of maintaining colonization.

From pre-Colonial times, Euro-American views of Indians as possessors of mythic stealth and courage, qualities that were promoted in popular fiction, Holm writes, “…whites were infected with the ‘Indian scout syndrome.”

He cites as example Colonel James Smith’s 1799 description of a battle where a Delaware chief and some warriors, surrounded and trapped in a cabin, chose death rather than surrender. When Smith threatened to burn the cabin down, the chief replied defiantly that he could “eat fire.” When the fire was set, the Indians came out fighting and were all killed.

“Whites apparently believed,” Holm writes, “that these mystical traits, to the extent that they existed at all, were genetically inherited rather than learned.”

Holm provides several examples of Indian scout syndrome operating in WWI, WWII, Korea and Viet Nam, at the highest national and military policy levels as well as at the unit level, stereotypes determining that the Indian soldiers are naturally best suited for certain types of combat roles, those that are likely to get them killed.

Euro-American forms and purposes of warfare were and are drastically different from those of Native Americans (and of many other indigenous societies throughout the world).

While people were certainly killed in wars fought between tribes, killing the enemy was generally not the goal. Death often brought open hostilities to an end.

The British introduced the practice of scalping and Native Americans responded in kind.

The European nations had created armies and navies who fought to annihilate their enemies, however, and introduced that form of warfare to the American continent.

As the British and French forces fought for control of the continent, tribes were forced to choose sides and inflict harm on each other in ways that they had not done before. Body counts replaced counting coup.

“Placed in the position of fighting for survival for the first time, increasingly equipped with the lethal technology of their ‘allies,’ and faced with a serious erosion of their territories because of expanding European ‘settlement,’ Indians began to kill both the European interlopers and each other in ever increasing numbers,” Holm writes.

Holm observes that the wars thus fought have taken terrible psychic tolls on its Native American veterans:

“…it would be well to emphasize the significance of ceremonies to the maintenance of Indian identity and the individual’s sense of peoplehood. Indigenous nations are holistic societies. That is to say religion, land, language, ceremony, and kinship structures are all part of an organic whole on which rests the continued well-being of the particular society.”

The psychic injuries continued, as veterans returned to Indian Country to find that their collective service to the nation is unrewarded by improved conditions for their People, writ large with the termination and relocation policies of the mid 20th century.

The American Indian Movement (AIM) arose in the course of the Viet Nam era, led by a number of combat veterans, intensely politicized by their experiences in Viet Nam and the “cognitive dissonance” they encountered between the national rhetoric and the realities of colonial life on the reservation.

Lastly, Holm calls for a new model: “Sustainable and truly Indian alternatives to US military services must be found. Otherwise, the next century will find us continuing in the mode developed for us during this one, not as free and self-determining peoples, but as patriots and pawns of the North American colonial order.”

Clearly, the answer lies in improving living and working conditions across Indian Country to more closely match those found off the reservation, and in implementing strategies to end the colonial relationships in this Land of Broken Treaties.

In this vitally important sense, nation-building should begin at home.

----------------------

All quotations in this essay: Tom Holm, Patriots and Pawns: State Use of American Indians in the Military and the Process of Nativization in the United States, Chapter XII of "The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization and Resistance", South End Press, M. Annette Jaimes, editor, a collection of essays, 1999

by Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon --Professor Tom Holm’s essay, “Patriots and Pawns: State Use of American Indians in the Military and the Process of Nativization in the United States”, goes far to explain why American Indians have enlisted and served in numbers that far exceed their percentage of the US population, despite the racist and hostile experiences that characterize the history of Native American peoples and the US military.

Native Americans volunteer for military service for the same array of reasons that non-Natives enlist, such as: family tradition, financial reasons, a desire to get away from home, to learn new skills, as a test of courage or to join battle with a specific enemy; i.e. Osama Bin Laden or Adolf Hitler. Professor Holm identifies several other factors specific to Native Americans to explain the phenomenon.

He also writes about the attitudes that shape military perceptions of Native Americans and that influence the roles that Indians are often called to serve in military operations, in how they are used.

Some Indian nations and Native American individuals have seen military service as a treaty obligation, a matter of honor; even though the US has rarely honored its own treaty commitments, their sense of honor requires their service.

Institutional factors, such as active recruitment efforts by the BIA and in Indian boarding schools, and discriminatory practices by local draft boards contribute to the enlistment numbers.

Holm briefly examines the relationships of ethnicity, political elites and the military. Throughout history, ethnicity has always been a vital part of the equation:

“In general, militaries not only protect the nation from foreign invasion, but promote the causes of and provide security for the hierarchical apparatuses of the state. In plural societies or imperial systems, state elites, both in uniform and out, have to judge which national or ethnic groups can serve in the military without turning the guns around and posing a threat to the state.”

Throughout history, ruling elites and nations have adopted many different strategies to incorporate vanquished peoples into their militaries, shaped by the dominant culture’s view of the subjugated ethnic groups, and by their perception of the potential threat. Holm suggests that an important reason that the US military has not felt threatened by its Native American service members is because the population is so few in number, such a small percentage of the total force.

Holm observes that incorporating Native Americans into the military is a method of assimilating them into the melting pot, of maintaining colonization.

From pre-Colonial times, Euro-American views of Indians as possessors of mythic stealth and courage, qualities that were promoted in popular fiction, Holm writes, “…whites were infected with the ‘Indian scout syndrome.”

He cites as example Colonel James Smith’s 1799 description of a battle where a Delaware chief and some warriors, surrounded and trapped in a cabin, chose death rather than surrender. When Smith threatened to burn the cabin down, the chief replied defiantly that he could “eat fire.” When the fire was set, the Indians came out fighting and were all killed.

“Whites apparently believed,” Holm writes, “that these mystical traits, to the extent that they existed at all, were genetically inherited rather than learned.”

Holm provides several examples of Indian scout syndrome operating in WWI, WWII, Korea and Viet Nam, at the highest national and military policy levels as well as at the unit level, stereotypes determining that the Indian soldiers are naturally best suited for certain types of combat roles, those that are likely to get them killed.

Euro-American forms and purposes of warfare were and are drastically different from those of Native Americans (and of many other indigenous societies throughout the world).

While people were certainly killed in wars fought between tribes, killing the enemy was generally not the goal. Death often brought open hostilities to an end.

The British introduced the practice of scalping and Native Americans responded in kind.

The European nations had created armies and navies who fought to annihilate their enemies, however, and introduced that form of warfare to the American continent.

As the British and French forces fought for control of the continent, tribes were forced to choose sides and inflict harm on each other in ways that they had not done before. Body counts replaced counting coup.

“Placed in the position of fighting for survival for the first time, increasingly equipped with the lethal technology of their ‘allies,’ and faced with a serious erosion of their territories because of expanding European ‘settlement,’ Indians began to kill both the European interlopers and each other in ever increasing numbers,” Holm writes.

Holm observes that the wars thus fought have taken terrible psychic tolls on its Native American veterans:

“…it would be well to emphasize the significance of ceremonies to the maintenance of Indian identity and the individual’s sense of peoplehood. Indigenous nations are holistic societies. That is to say religion, land, language, ceremony, and kinship structures are all part of an organic whole on which rests the continued well-being of the particular society.”

The psychic injuries continued, as veterans returned to Indian Country to find that their collective service to the nation is unrewarded by improved conditions for their People, writ large with the termination and relocation policies of the mid 20th century.

The American Indian Movement (AIM) arose in the course of the Viet Nam era, led by a number of combat veterans, intensely politicized by their experiences in Viet Nam and the “cognitive dissonance” they encountered between the national rhetoric and the realities of colonial life on the reservation.

Lastly, Holm calls for a new model: “Sustainable and truly Indian alternatives to US military services must be found. Otherwise, the next century will find us continuing in the mode developed for us during this one, not as free and self-determining peoples, but as patriots and pawns of the North American colonial order.”

Clearly, the answer lies in improving living and working conditions across Indian Country to more closely match those found off the reservation, and in implementing strategies to end the colonial relationships in this Land of Broken Treaties.

In this vitally important sense, nation-building should begin at home.

----------------------

All quotations in this essay: Tom Holm, Patriots and Pawns: State Use of American Indians in the Military and the Process of Nativization in the United States, Chapter XII of "The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization and Resistance", South End Press, M. Annette Jaimes, editor, a collection of essays, 1999

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)