LaDuke’s Earth Day Observations Resonate

Indian Country Today

By Carol Berry April 22, 2011

The American Indian activist and author spoke at the University of Colorado Denver for an early commemoration of Earth Day 2011, whose theme this year is A Billion Acts of Green, “our people-powered campaign to generate a billion acts of environmental service and advocacy before Rio +20,” according to the site.

For her part, LaDuke drew attention to some decidedly un-green practices, pointing out that the American economy consumes from a fourth to a third of the world’s resources but that there is “a vast amount of waste” in the petroleum economy that distorts the oft-repeated argument that renewable energy can’t keep up with demand.

“But why try?” LaDuke queried, adding that “empire is inefficient.” She pointed out that 90 percent of energy from the common lightbulb is in the form of heat and only 10 percent is light. “It’s a false argument that we can’t meet demand without buttressing an inefficient system.”

Food security is a problem when food travels an average of 1,546 miles from producer to dinner table, the price of gas goes up and food cultivation may require 15 times more energy to produce than is consumed, she said.

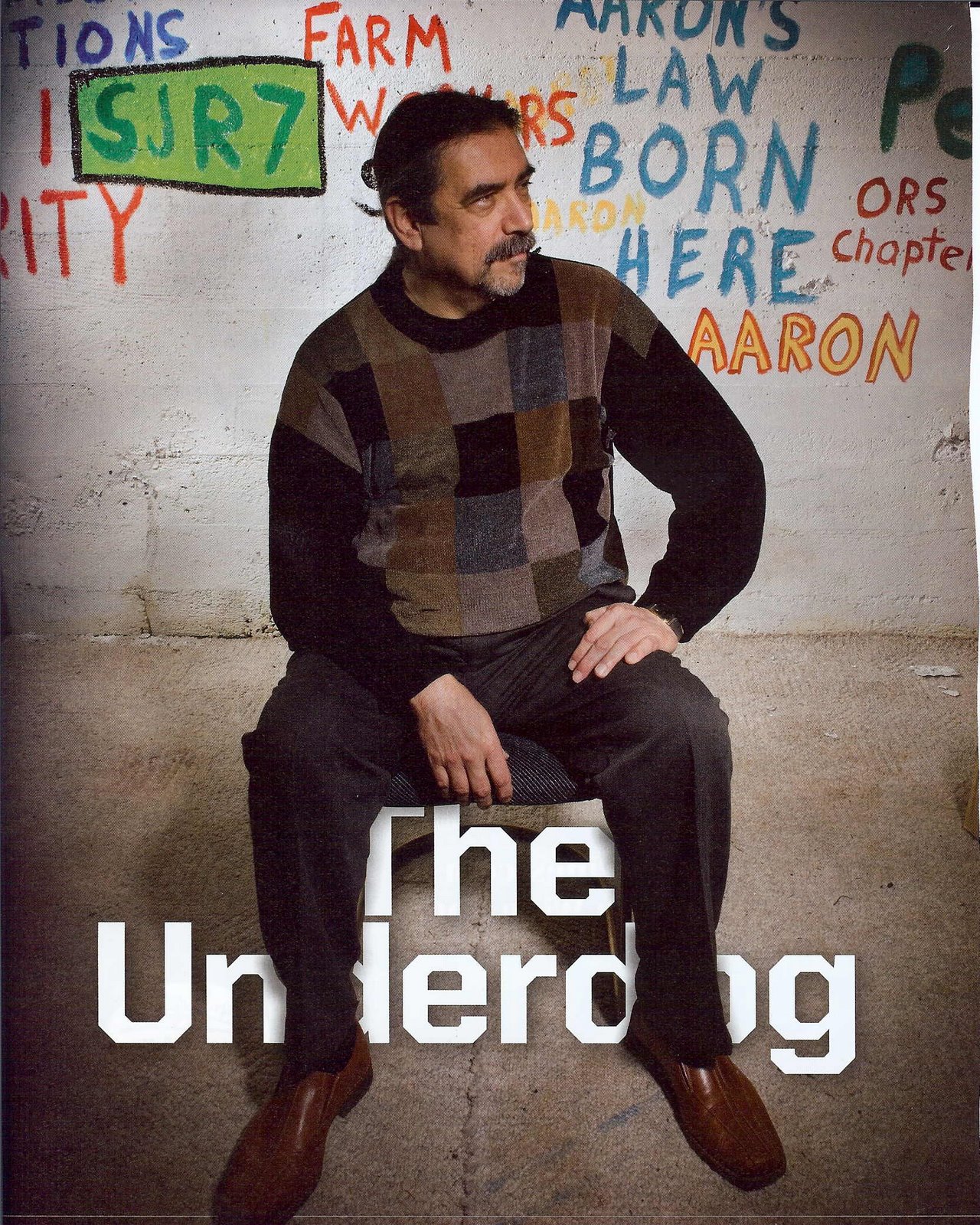

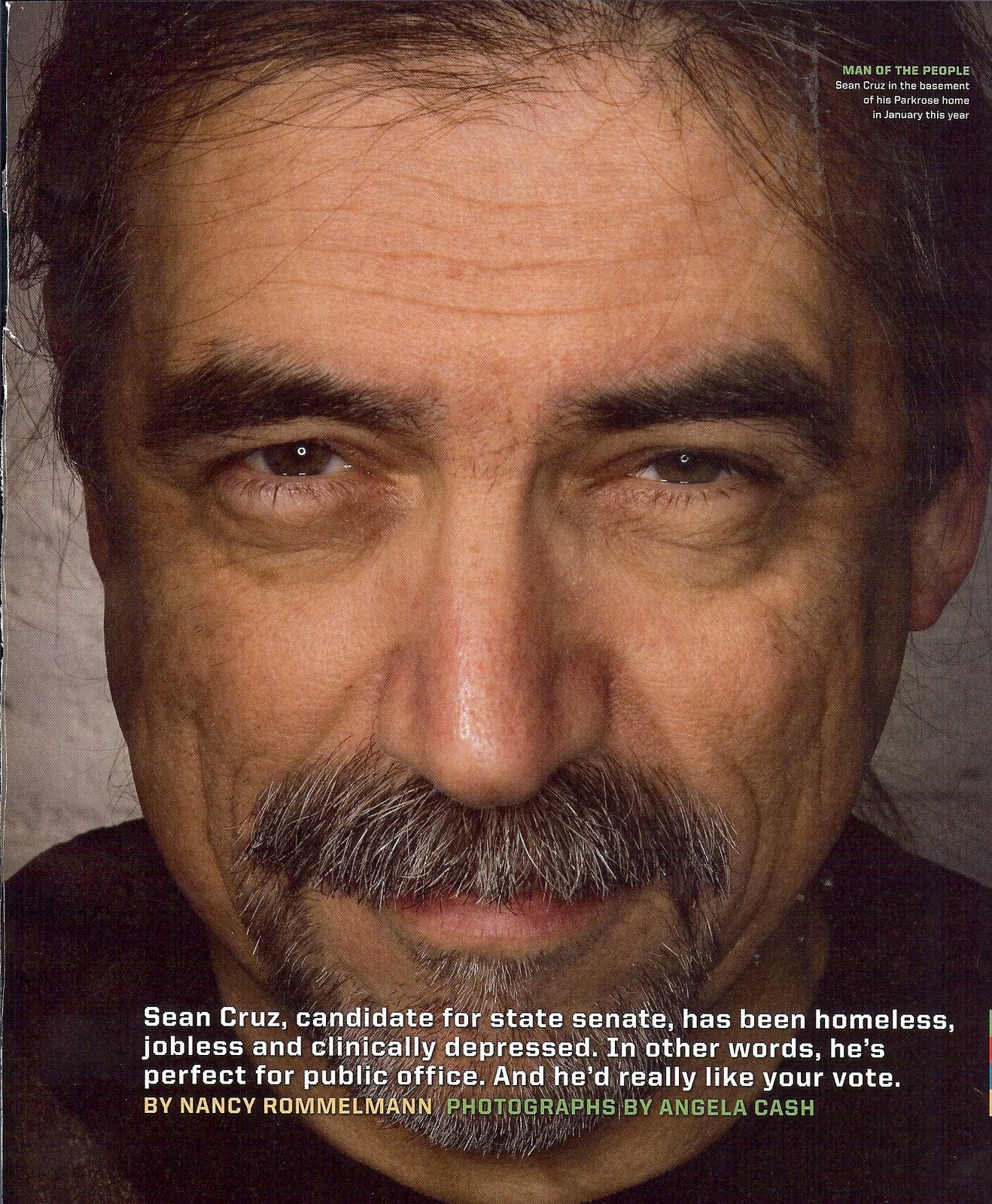

Although she does not hate the military and believes veterans should be treated with honor and dignity, LaDuke does “despise militarization because those who are most likely to be impacted or killed by the military are civilian non-combatants” and because toxins and chemicals have severely impacted Indian lands, she said in the preface of a book she has co-written with Sean Cruz, The Militarization of Indian Country, put out by Honor the Earth, an organization that works internationally on issues of environmental justice and sustainability. She is the group’s executive director.

The two-time vice presidential candidate on the Green Party ticket also said she is considering another run for office—this time for tribal council on the White Earth reservation in northern Minnesota, a move that would be compatible with her belief that change is local—and probably inevitable.

“I’m proud of the casino economy, but if you can’t feed yourself, I don’t know if you can be sovereign again,” said LaDuke.

LaDuke said a study on her reservation showed that 14 percent of spending for food was on-reservation, primarily at convenience stores, but 86 per cent went off-reservation to big-box markets or other food sources; because half of total spending goes outside reservation boundaries, the economy is “systemically flawed” and additional wages would not be a solution.

The answer is “re-localizing food and energy systems to have control over the economy and health in the face of rising food uncertainty,” she said, noting that one-third of people on her reservation have diabetes and half of the children are obese by the eighth grade.

LaDuke recalled that her late father told her, “Winona, you’re a smart young woman, but I don’t want to hear your philosophy if you can’t grow corn.”

Today she grows heirloom varieties of corn, as well as squash and other food crops, and harvests wild rice in an on-reservation food production enterprise that also includes maple syrup.

She touted the nutritional and traditional value of the older corn varieties, which include Bear Island Flint Corn, Seneca Pink Lady Flour Corn (“I grow it because it’s pretty,” she said), and Pawnee Eagle Corn, grown by Pawnee people living near Kearney, Nebraska, before their removal to Oklahoma. The corn, languishing further south, was returned to Nebraska for an indigenous garden at the Gateway Museum, where it flourished.

She also talked about climate change, noting that a two-degree increase in average temperatures in the northern latitudes could mean rising oceans and relocating Native villages, despite the fact that the cost of one such relocation was $400 million.

The U.S. has consumed 60 percent of its known oil reserves, and the vast tar sands in Canada are the “single largest industrial project in world history,” mining a Lake Superior-size area for the oil trapped in sand and clay and then planning to send it via the TransCanada Pipeline to Nebraska, where ranchers and legislators fear pipeline spills and the contamination of a shallow aquifer.

She was introduced by Glenn Morris, associate professor of political science at the University of Colorado Denver, who hosted her appearance, and the presentation itself was sponsored by American Indian Student Services of UC-Denver, Metropolitan State College and Community College of Denver.