By Sean Cruz

Portland, Oregon--

You are probably not aware that the Oregon State Police maintains a Museum of Missing Children.

Created in 1989, it maintains such a low profile that I did not learn it existed until the summer of 2004, eight long years after my four children had disappeared from Oregon, on their way to concealment in a series of remote Mormon enclaves in Utah.

I discovered the OSP Missing Children Clearinghouse website while preparing my testimony for the Senate Interim Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions, which held four meetings that year.

It was a shocking discovery, my first clue to the fact that no Oregon law enforcement agency maintains a list of missing or abducted children, not then and not now (see “Abducted child vs stolen car: A problem of priorities” for further discussion).

One would think that the OSP Missing Children Clearinghouse would have such a list, collected from and shared with local law enforcement agencies throughout the state, but that is far from the case.

The site contains a scant 41 names. Some have been missing for decades. The only name added in the past three years is Kyron Horman, last seen in the company of his stepmom, Terri Horman, in June.

Yet Portland has been making the national news recently for its prominence in the child sex trade trafficking business.

In September, Sharyn Alfonsi reported on ABC World News:

“Though Portland, Oregon is considered one of the most livable cities in the U.S., it also has a reputation as the national hub for child sex trafficking.

“In today's Conversation, ABC's Diane Sawyer and Sharyn Alfonsi talked about Alfonsi's trip to Portland and why middle-class children are getting recruited in a city with the largest legal commercial sex trade (per capita) in the U.S.

“Alfonsi visited the 82nd Avenue strip, also known as "The Track," where there are more than 100 massage parlors and strip clubs. She interviewed child victims their parents and even the pimps.”

These reports are clearly at odds with the OSP list. It is not known what set of circumstances would cause a missing or abducted child’s name to appear on the OSP website, but it would begin with a report from local law enforcement.

Most of the photographs of the 41 missing children on the OSP website appear to be school pictures, and there is a nostalgic sense of looking at old yearbooks, at moments frozen in time, as one gazes at these faces, all but one, Kyron Horman, completely forgotten by all but the once-child’s surviving family members.

There is no cold case squad for missing or abducted children; for most, there isn’t even a warm case squad. If they are still alive, most of these faces belong to adults now, and one can be sure that law enforcement isn’t looking for children-now-adults.

These are photos for a museum, with little effective purpose other than to underscore the fact that abductions are forever, that these are continuing crimes, crimes without end, regardless of the ages of the victims.

To be sure, the OSP Missing Children’s Clearinghouse suffers from inadequate funding, a condition made permanent by the voters themselves when they amended the Constitution in the 1980’s to shift funding from the State Highway Fund to the General Fund, and then made a habit of continually underfunding the agency, biennium after biennium.

Efforts to recover Oregon’s missing and abducted children and to make a dent in the child sex trade that is currently flourishing here are surely hampered by the failure to prioritize the children, a fault shared by state and local law enforcement agencies and by successive legislatures.

The most recent OSP Annual Performance Progress Report posted on the agency website makes no mention of missing children, nor does its proposed Key Performance Measures for the 2009-2011 biennium.

The OSP and the Department of Justice assured the Task Force on Parental and Family Abductions in 2004 that they would implement a rule requiring that all Oregon local law enforcement agencies report all cases of missing or abducted children to the OSP Missing Children’s Clearinghouse, because they were not doing so on their own.

They never implemented the rule, making this a good time to remind the Oregon legislature and law enforcement agencies around the state, as they plan for the coming 2011 budgeting bloodbath, of the mission of the Oregon State Police Missing Children’s Clearinghouse:

“The mission of the Missing Children Clearinghouse is to receive and distribute information on missing children to local law enforcement agencies, school districts, state and federal agencies, and the public. In 1989,the Oregon legislature mandated that OSP establish and maintain a missing children clearinghouse.

“The goal of the Missing Children Clearinghouse is to streamline the system, serving child victims and their families by providing assistance to law enforcement agencies and the public.”

Lest they continue to be forgotten, the names of Oregon’s 41 missing children:

The earliest name on the list is Brian page, missing since 1975

Christi Farni and Edward Nye comprise the Class of 1978

Jerry Johnson has been missing since 1982.

Joan Hall vanished in 1983

William Gunn disappeared in 1984

Jeremy Bright and Duane Fochtman have been missing since 1986

Walter Ackerson, Kacey Perry and Rachanda Pickle, Class of 1990

Thomas Gibson made the list in 1991

Ashlyn Wilson vanished in 1995

Annalycia Cruz was an infant weighing 14 pounds when she disappeared in 1996

Aryssa Torabi and Derrick Engebretson, Class of 1998

Five children disappeared in 2001: Shausha Henson, Yuliana Escudero, Kami Vollendroff, Eugene Hyatt and Shaina Kirkpatrick

Carlos Cortez-Leon vanished in 2002

Five more children disappeared in 2004: Karla Coronado, Miriam Cruz-Torres, Schnee Bedford, and siblings Takoda and Tiana Weed

Narcisa Bernadino has been missing since 2005

Five children made the list in 2006: Samuel Boehlke, Nieves Izquierdo-Olea, Esmerelda Salazar-Penaloza, Luis Adrian-Olea, and Yeni Fuentes-Garcia

Seven children vanished in 2007: Jesus Marina-Mendoza, Keely Gigoux, Maria Hidalgo, sisters Savanah and Sierra Ontiveros, Jamie Wiedeman and Jacob Thorpe

According to the OSP Missing Children’s Clearinghouse, no Oregon children were reported missing in 2008, 2009 or 2010, until Kyron Horman was abducted in June 2010.

Tell that to Diane Sawyer and Sharyn Alfonsi….

===========

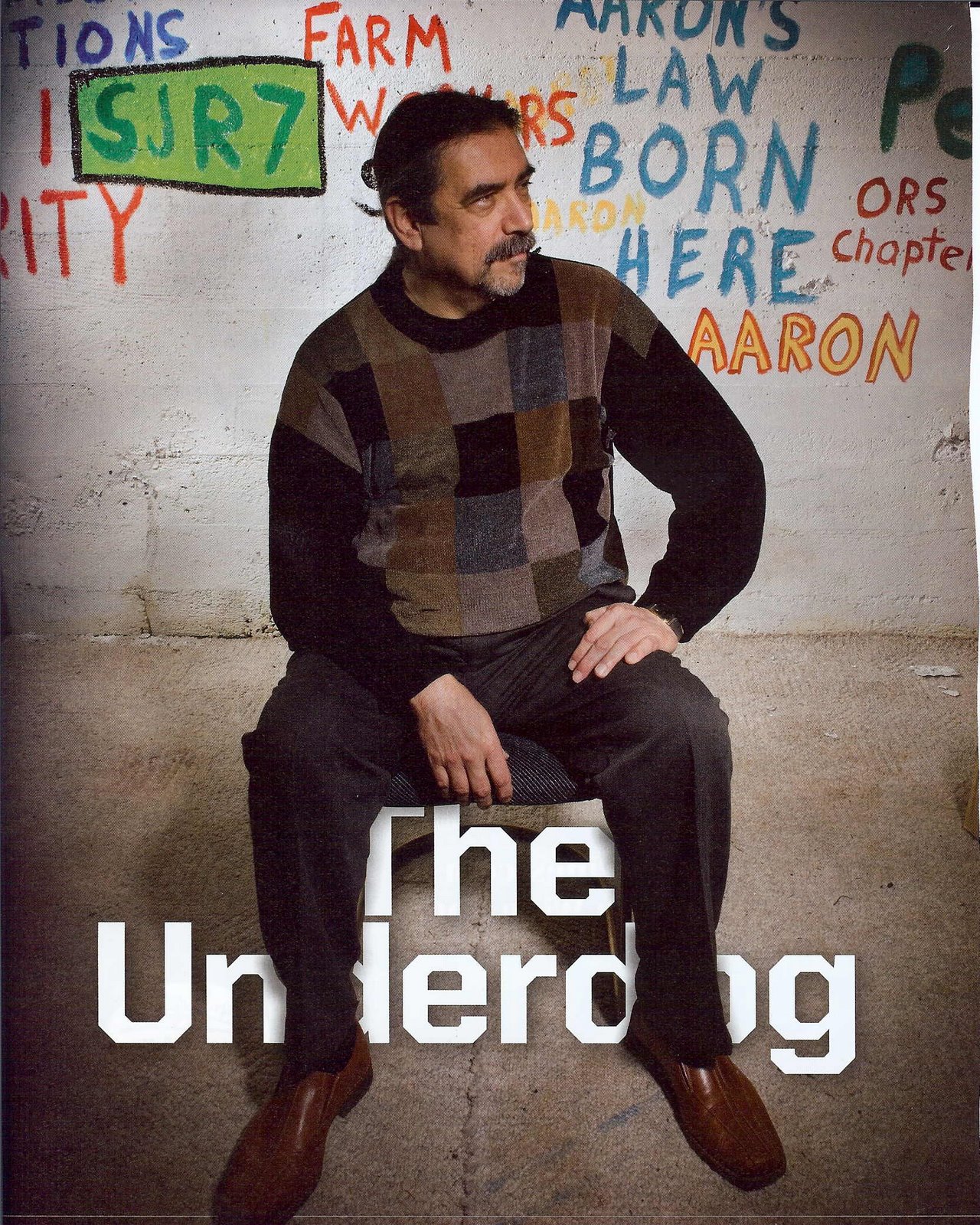

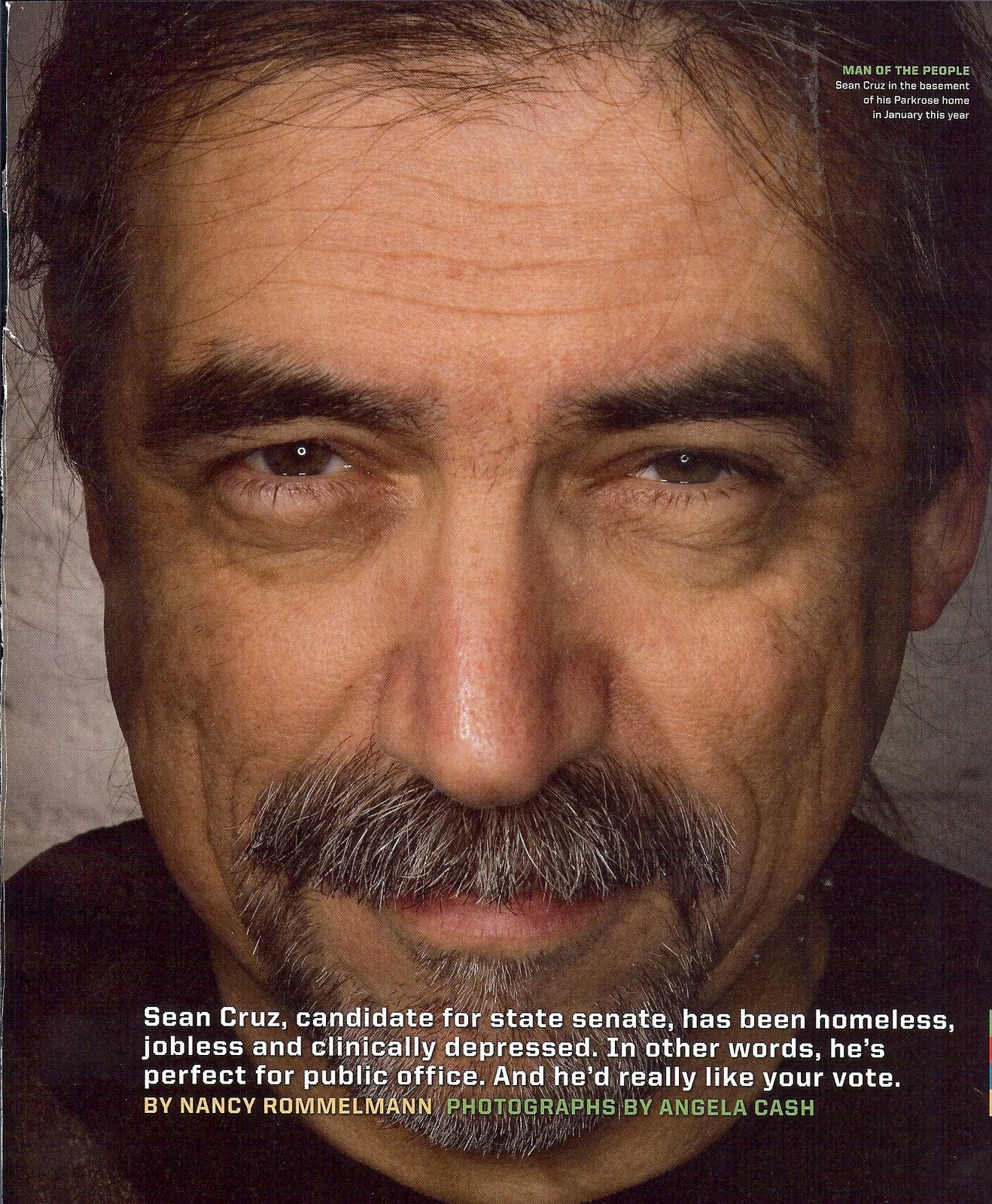

Sean Cruz led the workgroup on Oregon’s landmark anti-kidnapping statute Senate Bill 1041 “Aaron’s Law”, named for his late son Aaron Cruz. The provisions of the bill resulted in large part from the multiple failures of both the family law and criminal law systems in the wake of the abduction of his four children.

The bill was sponsored by Senator Avel Gordly and passed on a dramatic end-of-session unanimous House vote in 2005.

With Aaron’s Law, Oregon is the only state in the nation where abducting a child creates a civil cause of action.

Under Aaron’s Law, any victim can hold his or her abductor(s) financially accountable in civil court, including those who provided logistical, financial or planning support to the abductor(s) or who otherwise participated materially in the crime.

Sean hopes to see the provisions of Aaron’s Law applied nationwide and reduce the number of parental and family abductions from its rate of more than 200,000 child victims a year to zero.

He also believes that Aaron’s Law provides the legal means for victims of child sex trafficking to hold their pimps and other abusers financially accountable for their crimes, having violated the Custodial Interference I statute.

No information about Senate Bill 1041 appears on the OSP website.

Saturday, November 13, 2010

Oregon's Museum of Missing Children and the child sex trade

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment